- Home

- Edward Dee

Nightbird Page 5

Nightbird Read online

Page 5

“If she was that fragile, somebody should have been looking out for her. I’d like to know who.”

“What would that accomplish, Anthony?”

“Whoever it was should be called on it.”

A TV reporter stood in front of the Broadway Arms, explaining how Gillian Stone fell to her death. Ryan put his face between his knees. Leigh wrapped both arms around her husband. “Come on, we’re not going to mope tonight.” She reached for the clicker. “I can’t watch this anymore.”

The images faded to black. But the image unerased was the one in Anthony Ryan’s mind: of himself as he listened to the Utah Public Safety officer explain how their son, Rip, had died.

The official Utah verdict was called PIO, pilot-induced oscillation. Pilot error. The police had ascertained from witnesses that young Rip Ryan, in his inexperience, was unable to make his final turn into a turbulent wind. He hit the ground at approximately fifty miles an hour. In the state-of-the-art morgue of a western state, Ryan listened to the drone of official words as he silently begged God to let him change places with the broken body being caressed by his wife. Never in his life had Ryan felt so helpless, so useless. Leigh whispering hoarsely to their son, as if crooning a lullaby.

“Maybe nobody is responsible,” Leigh said as she stacked the Playbills back in the box. “I’m going to call my sister, tell her we’ll pick her up in five minutes.”

Somebody is always responsible, he thought. Who would tell the Stones that no one was responsible? He thought about them in the Bellevue morgue this morning. Did they think their daughter was only sleeping? He’d noticed that it always took an oddly long time for parents to react in the morgue. He didn’t know if it was the familiarity of the closed eyes or the absolute stillness. Or merely a few extra seconds of hope. How easy it was for parents to convince themselves, for those few seconds, that their child was only sleeping.

“Enough dwelling,” Leigh said. “Dwelling is not good for anybody.”

She grabbed his wrist and tried to pull him to his feet. He sat there looking up as she yanked. “On your feet, pally. Let someone else worry about who’s responsible. The only thing you have to worry about is where you’re taking us for dinner.”

The weight of being up for over twenty-four hours had descended on Anthony Ryan. Fatigue had left his emotions too close to the surface. He buried his face in his arm. He wanted to stay in this room where he knew the stories behind every framed picture, every souvenir and knickknack, every odd creak and groan.

“I need to be fed, Officer,” Leigh said, still pulling. “Something Italian and fattening as hell. Maybe a nice bottle of wine. A big bottle. We’ll all get stoned on that Day-Glo red you half Italians drink.”

“Dago red,” he corrected, and had to smile because his southern girl had said it the same way for over thirty years. “It’s called dago red.”

She yanked with both hands, grunting, as if pulling him out of jungle quicksand. Her back was almost parallel with the floor, head thrown back recklessly, gray hair flying. Ryan got up slowly, holding tight; he had to or else she would have fallen backward. When he was up, she wrapped her arms around his waist.

“Dago, Day-Glo, whatever,” she said. “We’ll get two bottles.”

7

The borough of Queens was named after Catherine of Braganza, the queen of King Charles II. She could have it back as far as Danny Eumont was concerned. On Thursday morning road crews had funneled Fifty-ninth Street Bridge traffic into one eastbound lane; it took Danny two hours to drive the olive green Volvo from home to his office.

Manhattan magazine, despite the facade of a P.O. box and a telephone exchange indicating Manhattan, was actually located in a fading industrial section of Long Island City, Queens. For a quarter of the price of Manhattan square footage, the fledgling journal rented the entire top floor of a two-story concrete block structure only two subway stops east of the East River.

Danny jogged up the steep and narrow stairway to the second floor. An auto body shop occupied the ground floor of the kind of building his uncle called a “taxpayer.” The magazine’s main office was empty, nine A.M. being too early for real journalists. The floor plan consisted of one long room, with private offices at the far end. Only editors and bean counters rated private offices. Danny’s desk sat in the big room, near a back window, overlooking a pyramid of used tires and a vicious one-eared mongrel restrained by an anchor chain. The only time he’d brought Gillian to the office, she’d gone out and actually petted the greasy, psychotic beast.

Ball-peen hammers pinged and air compressors whooshed as Danny opened and slammed his desk drawers, looking for his tape recorder. The recorder was the only reason he’d made the trip in the first place. He rarely used it, but this time he wanted verification of the impromptu interview he was about to spring on Trey Winters. Verification was the right word. Verification, because he didn’t trust Trey Winters. Not for evidence. Danny wasn’t in the evidence business. He wanted to set things straight for Gillian, tell her story. And after all, it was he she had called, nobody else. His uncle always said that life was a series of loyalty tests. He wasn’t going to start flunking them.

He found the recorder under a menu for Chinese takeout. The batteries seemed strong. He popped in a fresh microcassette. Then he checked his messages: nothing pressing. He did have three new letters he assumed were from cops. Most of his recent correspondence were reactions to his Todd Walker police brutality story. Usually he opened them with a carving knife, turning his face away in case of a malicious surprise. But no time for that now; he was running late for his own surprise. He decided it would be quicker to leave the olive parked here and take the N train back to Times Square. The smell of burned toast wafted out from the coffee room. He shoved the recorder into his pocket.

No more two shows on Wednesday,” Pinto said. “One show, we quit. Go home. You did too much yesterday, showing off for those Swedish bitches. It’s no good for you. Then you take too many pills, and that’s no good.”

Pinto had rubbed the entire tube of cream into Victor’s neck, arms, and back, and when the Russian wouldn’t massage hard enough Victor took over himself, his fingers pressing deeply into his flesh, kneading the muscle, digging underneath his shoulder bones, trying to squeeze the nerve endings themselves. The spasms were visible, the muscles almost jumping through the skin.

“Shot of cortisone straighten you right out,” Pinto said. “I’ll drive you to the accident ward. One shot you’ll be old self.”

“I have things to do.”

“People to see,” Pinto said. “I know all about it.”

“You know nothing; what do you know?”

“I know something with you is always up. Trouble is coming, that’s what I know.”

Pinto helped him get his shirt on. Victor wore a starched white shirt with a high collar. White shirts accentuated his tan, lit his face. He believed that a man with good skin should wear white, high around his face, especially turtlenecks. Victor could feel the warmth of the cream tingling on his skin, as if itching from a wool sweater.

“I’m sorry about the act today, Pinto.”

“Just go. Go to your important business. Thursday’s not so busy anyway. I’ll do a solo today. Not to worry.”

The bone-deep pain returned in full before the D train left the Bronx. By the time he got to Times Square Victor was desperate, his white shirt soaked with sweat. He’d taken only one pill before he’d left home, thinking it would be enough. The pain had returned too quickly.

He bought six little red pills from a pregnant woman in a doorway on Thirty-ninth Street and took three immediately. They weren’t his usual muscle pills, but by the time he got to the overhang of the hotel he was breathing easier.

Victor realized that he’d caused his own problems yesterday, starting his act without warming up. Then he’d overdone it. From the beginning he was too keyed up, too jazzed from the events of the night before. He’d put everything into the per

formance, showing off for the crowd, tossing the bowling balls higher than it was wise to do. Showing them what a former Barnum & Bailey headliner could do. The women, he’d heard the women squealing with pleasure. They should have seen him in his trapeze days.

Yesterday brought back the old days, and as always, he fed off the spotlight. But it was the end for him. Not even if a miracle took the pain away would he ever again beg an unappreciative street audience for loose change from their pockets. For their crumbs. No más.

In his hand Victor held the second installment of his golden egg. It was an envelope containing great discomfort for a very rich man. A man rich enough to spend a little to buy his own peace of mind. Victor had no desire to hurt this man. But they could ease each other’s discomfort. It was a simple business deal; he’d said as much in the note. Simple business. Done every day in this city. No worse than the stock market or General Motors. In fact, much less greedy. Mr. Trey Winters would see that his request was reasonable.

Victor felt better with each passing minute. Everything coming up rosy, as his friend Pinto always said. He almost smiled as Trey Winters came down the steps of his office. Victor knew that Winters met business associates every day at this time in the hotel coffee shop. Winters was right on time. Everything coming up rosy. Victor pulled the hat down tight on his head and adjusted the dark glasses. He planned to follow him into the hotel, hand him the envelope, and walk out the front door onto Broadway. Disappear into the crowd, just like last time at the Mexican restaurant.

Winters stopped at the rear entrance of the hotel. A young man had caught him as he was about to enter the revolving door. Winters appeared startled. The young man shuffled his feet and gestured with his hands. Victor wondered who he was. Then, Winters stormed into the hotel, an angry look on his face. Victor waited, the envelope that would change his life still in his hands. He felt his own fury erupting.

* * *

Danny Eumont’s timing was impeccable. Just as he came around the corner he spotted Winters walking into the driveway underpass of the Merrimac Marquis. He sprinted to catch the tall, lanky Broadway producer. Winters spun around and did a half pirouette.

“Sorry, Mr. Winters,” Danny said. “Didn’t mean to scare you.”

“You did a damn good job of it.”

Winters patted his long fingers against his chest. His theater-trained voice boomed with amplified resonance under the hotel. Danny had no doubt his tape recorder would pick it up easily. He handed his business card to Winters.

“I’m doing a story on Gillian Stone,” he said. “I wonder if I could talk to you for a few minutes.”

“I’d be glad to. Call my office and make an appointment.”

Except for a meat truck and one taxi, they were alone in the block-long underpass that was created to let vehicles pick up and drop off hotel guests without interfering with traffic on Broadway. Danny stepped out of the path of the departing taxi.

“I’ll call for an appointment,” Danny said. “But just a few short questions. I’ll be quick.”

“I’m running late right now.”

“About the rumors that Gillian was taking drugs, everybody I talk to seems to think that they’re false.”

“Whom did you speak to?”

“People close to her. Very close.”

“They couldn’t be that close. What magazine did you say you were from?”

“Manhattan. It’s on the card. Mr. Winters, I also have information from that same reliable source that you were sleeping with Gillian Stone. Could you comment on that?”

“That’s a rude, insulting question. Who the hell are you?”

“My source swears you were sleeping with her.”

“Your source and you can both go to hell.”

Winters turned gracefully and moved toward the revolving door.

“Don’t you want to know who my source is?” Danny yelled.

Not much of an interview, Danny thought as Winters disappeared through the whumpf, whumpf of the revolving door. He’d taken a shot, hoping Winters would be vulnerable so soon after Gillian’s death. It was a long shot, but he’d thought maybe Winters might lose it, say something stupid. His uncle always said the most truth was gathered in the hours immediately after the crime. The longer you waited, the more everyone hardened up, lawyered up. Stories got set in stone.

Danny walked along the sidewalk that edged the hotel side of the underpass. He stopped at the top of a stairway leading under the hotel, where the driver of a refrigerated truck had been sliding boxes of filet mignon down a metal chute. Danny used the truck for cover in case Winters came back out. He began playing back the tape. Danny’s voice sounded small in comparison with that of Winters. The conversation was short. He played it again.

The first thing Danny felt was the man’s wetness against his back, the heat from his body. Then the arm around his throat. He grabbed the tape recorder out of Danny’s hands. And shoved. Danny flew headfirst, reaching for anything, clutching only air. His left knee slammed down on the metal chute, his right knee missed the chute, and he spun right and tumbled down the steps, twisting as he grabbed a pipe with his right arm and heard the pop. He came to rest on the stacks of filet mignon, his right shoulder directly under his chin. He closed his eyes.

8

How’s Ryan’s nephew?” Chief of Detectives Paddy “Roses” Ferguson said without looking up. He’d heard Joe Gregory’s signature knock on his open door.

“Feeling no pain,” Gregory said. “They didn’t admit him. We brought him home from the emergency room, put him to bed. I told him he was lucky, his first mugging and all he lost was a tape recorder.”

The Chief, known to his old friends as Paddy Roses, shoved a file in his bottom desk drawer, then waved them in, pointing to the chairs.

“The kid’s pretty banged up,” Ryan said. “Dislocated shoulder is painful.”

“I coulda fixed that myself,” Gregory said, raising his own arm to demonstrate. “I watched the surgeon at St. Luke’s. Nothing to it. All he did was pick his arm up and twist, then he snapped it in. Like this. Rolled it back… then craaaack! Sounded like a gunshot in an alley.”

Ryan and Gregory belonged to a small cadre of experienced detectives personally assigned to the Chief’s office. They handled high-profile homicides and crimes that lingered on the front page. Informally they were referred to as the “Political Response Team.”

“The mugging thing is a little hinky,” Ryan said. “The guy didn’t take his cash, just the tape recorder. Danny had just finished interviewing Trey Winters, and like a dope, walks ten feet and starts playing the conversation back. The guy comes up behind him, grabs the tape recorder, and shoves him down into the cellar.”

“I’ve seen rookie undercover cops do that,” the Chief said. “They can’t wait to hear their own voices on tape.”

“So waddaya figure, pally, Winters’s bodyguard sees it and coldcocks him?”

“Makes more sense than a mugging.”

“Find out if he has a bodyguard,” the Chief said. “We’ll throw the prick in a lineup.”

“The kid didn’t see shit, Paddy,” Gregory said. “All Danny knows is the guy was strong and smelled like Vicks VapoRub.”

“Vicks VapoRub?”

“That’s what he says,” Gregory said. “I say, mugger or not, you gotta admire the work ethic. Chest congestion, bad cold and all, he’s out there hustling.”

“I was just hoping some cop didn’t do it,” the Chief said.

Longtime New York City cops refer to the people with whom they started their careers by saying, “We were cops together.” It’s a specific identification of a specific time: the rookie years in uniform. Chief Paddy Ferguson and Joe Gregory were “cops together” in Brooklyn, where the Chief earned his nickname because his preferred drink was a lower-shelf whiskey called Four Roses with a water chaser. In the days when foot cops drank free and freely in uniform, Paddy, after first checking his post for Internal Affairs spies c

alled “shooflys,” would back into local bars, in a Rockaway version of the moonwalk, while knowing customers crooned, “Roses and water, roses and water.”

“How about this actress thing?” the Chief said. “We closing that one?”

“Just a couple of loose ends away,” Gregory said.

“I hate that phrase, ‘loose ends.’ Is it still classified a suicide, or am I out of the loop, as usual?”

“Apparent suicide,” Gregory said. “Until we can explain the sticky substance we found on her mouth.”

“What sticky substance? Licorice, Jujubes, what?”

“Stickier,” Gregory said. “We can’t rule out the possibility it’s glue residue from tape. Somebody could have taped her mouth.”

“What’s wrong with that?” the Chief said. “I put tape over my old lady’s mouth all the time.”

“But you don’t toss her from eighteen stories up.”

“That’s because we live in a split-level.”

When relaxed with old friends, the Chief was Paddy Roses, the cigar-chomping street cop. But on cue, the handsome Irishman could transform himself into the very model of a modern major police executive: the leader of the largest metropolitan detective force in the world… Chief Patrick Ferguson. Informed, articulate, suave, positively elegant.

“I don’t want a big Hollywood production made out of this case,” the Chief said. “The news gets a whiff something’s wrong here, they’ll start making shit up. What’s the story on this drug thing? Was she a user or wasn’t she?”

“I read the interviews of Gillian’s friends in the show,” Ryan said. “None of them mentioned anything about drugs. One woman says she had mood swing problems. Nothing stronger. They all say she was a doll to work with.”

“That’s what friends are supposed to say,” the Chief said. “When I die I expect you guys to say I was an Irish American saint.”

“She didn’t have any needle marks,” Gregory said, shrugging. “No drugs found in the apartment. We’re waiting on toxicology.”

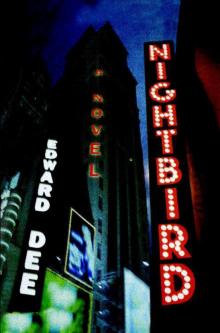

Nightbird

Nightbird